Special Note: Today’s edition of Aloha Friday with Fr. Tim contains some strong language. Your discretion before choosing to read (or listen) is advised.

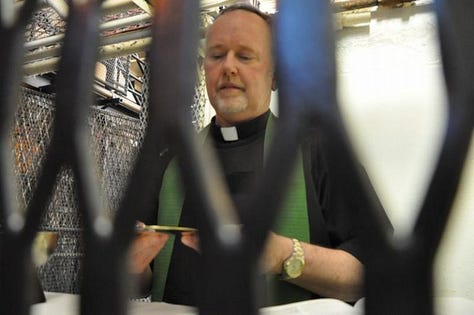

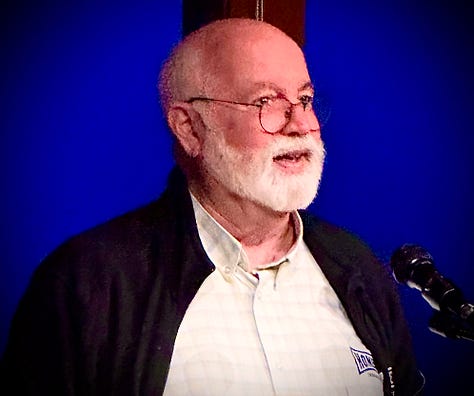

There’s a whole lot I admire about the Jesuits, also known as the Society of Jesus. I was fortunate to study with Jesuits. Because of the ecumenical nature of my seminary (the Church Divinity School of the Pacific) at the time, I was fortunate to cross enroll at the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University. I took my theology classes from Jesuits, along with a number of scripture, prayer, and pastoral care classes. This included my prison ministry class, which brought me inside the walls of the largest death row in the western hemisphere, located at California’s notorious San Quentin State Prison. I appreciate Jesuit spirituality, which is largely influenced by the spiritual exercises taught by Jesuit founder Ignatius of Loyola. I also appreciate that the Jesuits are down to earth. They rarely wear clericals. In fact, Jesuit author Fr. Jim Martin has said he wore his Jesuit habit exactly one time: the only time he was required to do so. Jesuits also are more ecumenical than many Roman Catholic religious orders. I have seldom met a Jesuit who was not willing to share Holy Communion with Episcopalians. Jesuits I have been fortunate to encounter include Fr. Martin, who publishes America Magazine, Greg Boyle, who founded Homeboy Industries, and George Williams, the now retired chaplain at San Quentin.

One of my Jesuit theology professors was Fr. K. (I’ve decided to refrain from including his name to protect his identity. The Internet is a wild place!). He was a passionate teacher who didn’t hold back when something bothered him. In fact, I’ve never met a Jesuit who held back. Once, during class, someone asked about the legitimacy of a bleeding host, something not uncommonly discussed in Roman Catholic circles. As legend has it, consecrated hosts have been said to resemble human flesh and even bleed. However, these events are not known to have ever been observed in a way that has been documented by science. Often, they are explained by some kind of bacterial or fungal growth on a host, which has usually been on display in a monstrance. These growths can be red in color and resemble blood to the onlooker. (For the record, I have witnessed a consecrated host become moldy while displayed in a monstrance, so this seems like a reasonable explanation to me. Following protocol, I dissolved the host in water and poured it down the piscina). While I don’t limit the power of God, and a “bleeding host” is certainly something God could choose to permit, the concept of a bleeding host misses the point of the sacrament, which should be shared with the faithful. When the question about bleeding hosts arose, K. slammed his fist down on the desk, and said, “with all due respect, that’s bullshit.”

“Whoa!” we all thought. That’s quite an unexpected response from a priest! But we were also young, aspiring priests-in-training. Now, I’m sure we all use such language. Regularly. And with good reason! But then? It took us off guard. Where did this response come from? I didn’t know then. But now that I’ve been ordained for a number of years and I’ve had a lot of conversations with people about theology, I kinda get it. Sometimes people have theology that is, with all due respect, bullshit. And this bullshit theology (or, to use a term that is softer on the ears, bad theology) harms people. It doesn’t necessary harm the people who spout it, by the way. It harms its intended targets. Those people these wannabe theologians try to place in the category of “other.” Those whom they choose to exclude. When it comes to bullshit, it usually sounds something like, “I’m good and you’re bad.”

Because I’ve become much more active on social medial lately, I’ve had more and more encounters with people around the world. This includes people I never knew. It includes people I, quite frankly, wish I still didn’t know. But sure enough, these people have crossed my path. And usually when they cross my path, it isn’t because they’re happy about the theology I teach, especially the theology that draws inspiration from the 25th chapter of Matthew’s gospel. In Matthew’s gospel, we are reminded to advocate for those whom society chooses to place on the margins. The people who place them there, frankly, look a whole lot like me. In today’s context, the people shoved toward the margins frequently include immigrants, people of color, children, the sick, the poor, the hungry, the thirsty, the imprisoned, women, the LGBTQ+ community, and anyone else who has been shoved aside. And might I add that one of the reasons I was attracted to come to St. John’s was because it is a parish with a strong desire to serve those on the margins. But what I find odd (and to be, with all due respect, bullshit) is that so many people take time out of their otherwise busy day to tell me that I, along with the people to whom I’m ministering, are going to hell. To steal something from my theology professor that I can share with those who would have the audacity to condemn anyone to hell, with all due respect, bullshit!

Hell is one of those things that some Christians like to talk about a whole lot. In Roman Catholic circles, there is even a place we can go after we die that is kind of like a “temporary hell”. It’s called purgatory. The word comes from the Latin for purging or cleansing, and purgatory is taught to be a place where we go if we’re just quite not ready for heaven. If that sounds weird, just wait until we get to limbo! Limbo is a place the Church of Rome tells believers they will go if they have not been baptized. Why? Because that church teaches that salvation is only available through Jesus Christ, but damnation is not possible for those who have not committed grave sin. The most frequently cited example of the souls in limbo are the souls of infants who died before baptism. And, I have to say that these concepts, with all due respect, are bullshit.

Why? Well, because God’s grace abounds. Is it possible that such places (or, rather states of being) exist? Sure. God can do anything God wants. I would never limit the power of God. At the same time, God’s message to us is that he does not want us to be in a state of separation from him. Imagine how a human parent responds to their child committing a crime. While the parent might not be pleased about the child’s behavior, the parent still loves the child and wants no harm for the child. Ted Bundy, who killed dozens of women in the 1970s, was the kind of guy who many people in the country despised. During his visit to Florida’s electric chair in 1989, crowds of people surrounded the prison to cheer for his death by electrocution. The cheering was so loud that witnesses inside the death chamber claimed they could hear them. And yet, while the rest of the world celebrated the demise of one of the worst serial killers in American history, the final words from Louise Bundy to her son were, “You’ll always be my precious son.” No matter what he had done, and no matter how bad his actions were, Ted’s mother loved him to the end. And if a human mother has the capacity to continue to love her child, a child who committed heinous acts that are far too graphic for me to describe in this publication, then don’t we believe an all-loving, all-compassionate God would have compassion for God’s children, no matter what? I believe so.

You see, it’s a misnomer to think of hell as a place. Instead, it’s a state of being. And I’m not suggesting we can’t end up in a state of hell. What I’m saying is, neither God, nor God’s people, condemn us there. If we arrive in hell, it’s because we’ve become separated from God. And it’s that separation itself that we call hell. Even if we arrive in that state, God’s love for us persists. And, despite what generations of theologians might have taught, I tend to believe we can leave that state and return to God when we recognize that we’ve become separated. Why? Because like the mother who can still love her son before his date with the electric chair, God can continue to love us and bring us redemption.

All those images we have of hell as a place of fire and burning and suffering? Those are images that come to us from Dante and his Inferno from the Divine Comedy. Dante’s imagery is so powerful and so well-known that virtually any time any one of us pictures hell in our minds, we’re imagining the scene as described by Dante. But there’s another piece of Dante’s Inferno that is perhaps more useful to us. It’s a sign. Above the gates of hell, the sign reads, “Abadon hope, all ye who enter here.” And there it is. The definition of hell. A state of being where we have no hope. Where we have no love. Where we have no joy. When we reach those stages, it can truly feel like our own personal hell. But it’s important for us to remember: if and when we enter that state, it isn’t because God sent us there. It’s because we’ve wandered away from recognizing God’s goodness. And I’ve got news for you. It isn’t because God stops being good. It’s simply because we’ve ceased to recognize it. But can’t we still turn back when we realize we’ve abandoned all hope? All love? All joy? I would have to say yes.

When Jesus tells us to repent in the gospels, the word he uses literally means to change direction. It doesn’t mean we need to get on our knees and grovel. It doesn’t mean we need to whip ourselves with chains or a cat o’ nine tails. It doesn’t mean we need to sleep on a mattress of nails, or to abstain from pleasurable foods. It means we turn away from those ways that brought us there. And you wanna know another thing? God isn’t petty like we are. God doesn’t send us to the electric chair and celebrate our demise while wearing shirts that say, “It’s Fry-Day!” Like the father of the Prodigal Son, God slaughters the fatted calf and throws a big party for us when we repent and turn our course around. God is our biggest fan. God is our biggest love. God is our biggest cheerleader.

And while some people have a hard time grasping this idea and falsely claim that it not only leads people astray but also justifies bad behavior, that is, with all due respect, bullshit. Because when we recognize the love of God in our lives, and we reflect on the goodness of God, then we are simply incapable of bad behavior. People who do evil things exist. Ted Bundy was a real person. But Ted Bundy was also a beloved child of God. A child who was very badly broken. A child who was very badly damaged. A child who was ill. A child that human society decided ought not share the oxygen we breathe any longer. And while Bundy’s actions were sinful, disgusting, and grotesque, we must remember that illness is not sinful. If I choose not to do the things Bundy did, it’s because I am well enough to recognize that those things are wrong. Anyone who performs acts of evil is clearly not well. And if those people are well, then guess what? It still isn’t our place to condemn them to an eternity in hell. As God’s creation, we answer only to God.

Should we permit bad behavior? No. So how do we know whether a behavior is bad? We can start by asking about our intentions and about its results. Is my intention to harm you? Is the result harmful to you? If these two things are in synch, then it’s probably bad behavior. If my intentions are to harm you, even if you are not harmed in the end, then it’s probably bad behavior. If the result is that I harmed you even if I didn’t intend to? Well. That one brings us a lot more gray area. If I drive intoxicated, I’m probably not intending to harm you. But my decision to drive while intoxicated is a harmful decision. And the truth of the matter is, we always want to work toward having good intentions combined with good actions. Not so that we will be rewarded. But because we acknowledge God’s goodness and favor toward us, and because we want to perpetuate that goodness.

Don’t follow theology that is, with all due respect, bullshit. God is good. At all times and in all places. Yes, even when we commit sin, God is good. No, that is not justification to commit sin. If we’re avoiding sin simply to earn some kind of reward, then we’re doing what Jesus tells us to avoid doing in Matthew 6. We’re not “good” for the sake of earning a reward. We’re good because God is good. And because God is good, God will lead us away from hell. Provided, of course, that we don’t want to end up there.

Perhaps Sarte’s No Exit might be a better description of hell